“I don’t really want to delve into previous concepts,” Pragmata producer Naoto Oyama tactfully offers, after I prod at the prickly topic of the lengthy development of Capcom’s latest weird and wonderful offering.

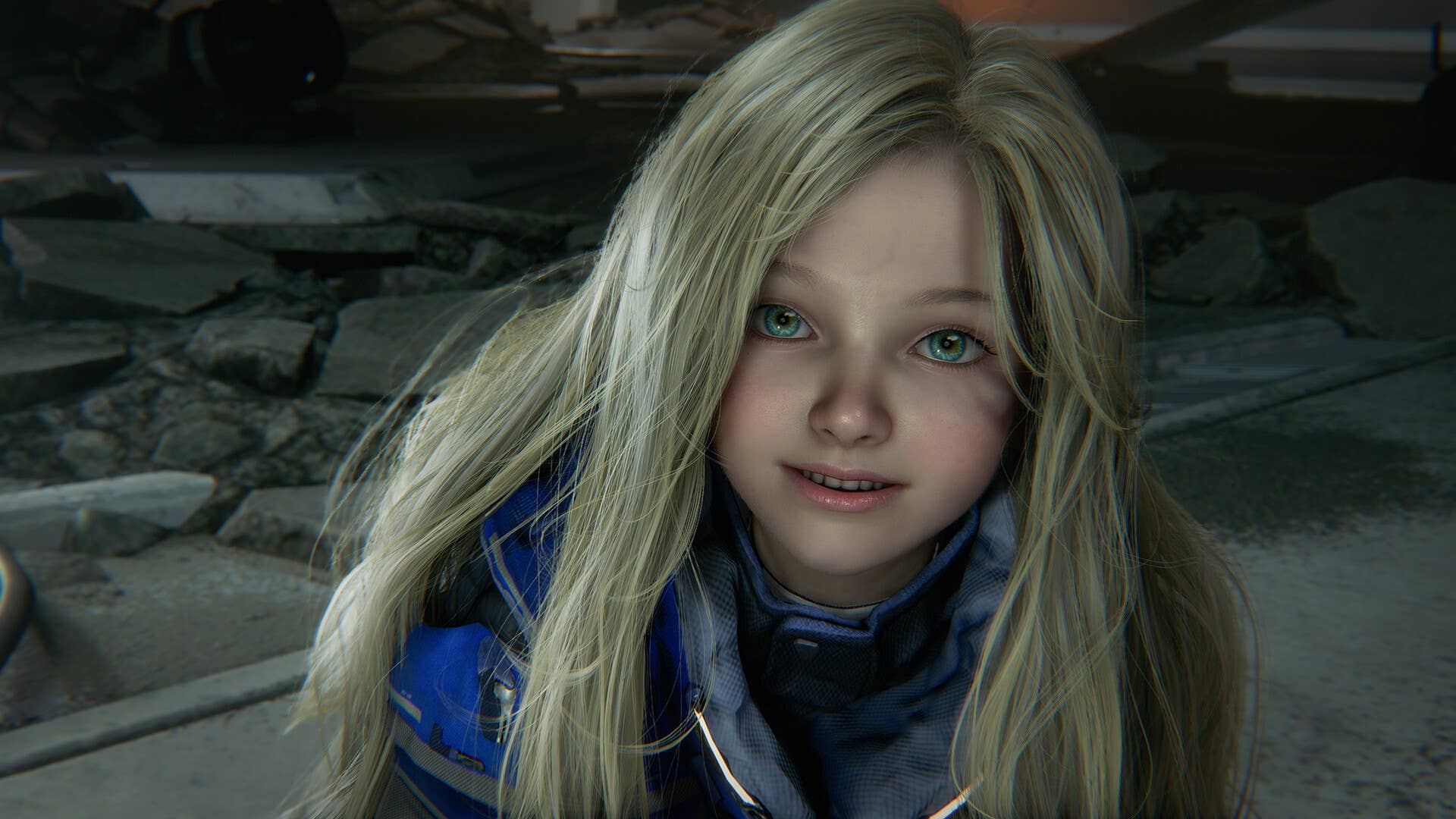

This mysterious game about the unlikely pairing of a spacesuit-clad bloke and a barefoot young kid (who is, of course, actually an android) has been rattling around for years. First announced in 2020, it was originally slated for a 2022 release. It was then shunted to 2023, then delayed indefinitely. Now, it’s locked in for a 2026 release. Perhaps understandably, Oyama doesn’t really want to talk about all that.

“Just verbally it might sound like, ‘oh this was great and that was great’ – even if on the whole, in the game, it didn’t work,” the amiable producer, who also worked on Dragon’s Dogma 2, explains. “So we’re going to skip over talking about what we had in the past and delve into what we have here today.”

Which, y’know, fair enough. That tracks, especially in an era where many have a low desire for context and a high affinity for outrage. At the same time, though, Pragmata’s extended development is fascinating – and arguably key to the game’s clear successes.

To see this content please enable targeting cookies.

As has been touched on in two separate Eurogamer hands-on previews since the game broke cover in June, Pragmata is weird, wonderful, and unique. It’s the sort of genre mash-up and mechanical melding that is seldom seen from big-budget, big-money publishers like Capcom.

Experimental concepts like this, bluntly, are usually reserved for indie games. Such a development path is often reserved for smaller-scale game jams or private, never publicly-shown experimentation in the depths of company headquarters – not for games announced with a massive splash in a platform holder broadcast. Pragmata is just that, though – and it perhaps speaks to the strengths of Capcom and its increasingly sure-footed position that it has been willing to allow a team to iterate and experiment with this strange new property.

“The first trailer we put out back in 2020, that was our first base concept trailer. From that base concept to create something that we think is fun, that we think people will really enjoy – it’s taken us a bit of time,” Oyama explains via the Japanese-to-English interpretation of Edvin Edsö, a fellow producer on the title.

“We might have had a concept in the beginning that was fun for a part of the game, for the initial part of the game – that fun might not have reached the entire, full game when we looked at the full picture of it. Having something that’s fun all the way through the game is something we reached towards throughout development.”

That core concept which has survived for the entire development is of course Pramata’s core conceit – the collision of worlds that is the hulking Hugh the the diminutive Diana. Hugh can control a variety of weapons and blast things. Diana hides over his shoulder and hacks enemies. Diana’s hacks aren’t truly enough to take down enemies on their own, but nor are Hugh’s ballistics. Powers combined, the duo has a chance.

I don’t want to retread our previews, but suffice it to say that this results in a curious and engaging system. Squeezing the left trigger to aim at an enemy offers two options – mashing the right trigger to fire away with Hugh’s equipped weapon, or using the face buttons to solve a small puzzle as Diana in order to hack the enemy. This must be undertaken in real time – juggling movement, enemy awareness, two different mechanics, and in a manner of speaking two different characters.

“The general concept of Hugh’s shooting – action – and Diane’s hacking – puzzle – that’s been part of the base concept from the beginning,” Oyama reiterates. “But getting that concept into a game system that’s fun – that took us a bit of trial and error to get to what you see today. Early on, the hacking wasn’t as you see – it was a different sort of style.”

Certainly, one can see where all of that iterative development time went. It would be very easy indeed for a game with a setup like this to be a totally confusing hot mess – but it isn’t. Pragmata is quirky, but the short demos I have experienced so far are nevertheless a joy. The vibes exuded are those of a game that has fallen out of another, more experimental era – from a time when genres were less defined and people were inventing new ones with reckless abandon. In this I find Pragmata instantly enormously refreshing, even if its idiosyncratic core might put some players off.

For this beat, the one thing that differs in the Pragmata hands-on to the previous I’d experienced is the addition of a boss battle. I enjoyed what I had to play before, but the boss really helped to elucidate the reasoning behind some of Pragmata’s weapon design – and how its systems might work across a full-length game. Where the previous demo had me marvelling at a very neat and tightly-executed gimmick, in experiencing a boss fight I now feel I can see the path for the full experience, so to speak.

“Once you see the boss fight, you can more fully see the entire experience,” Oyama agrees when I recount my experience to him.

Let me give you an example. Hugh’s Shockwave Gun is basically a shotgun, but it’s a real slow reload even by shotty standards. I didn’t feel very inclined to use the more powerful weapon on normal enemies due to the reload speed – but in a boss battle where regular and repeated hacking is required, those long reloads actually help to give the encounter a textured ebb and flow.

Oyama gets into that a little more, explaining to me how Hugh’s weaponry works. It’s all vaguely cagey stuff – only a tiny fraction of the game has been shown, and the developers clearly don’t want to reveal any unannounced kit. Broadly speaking, though, Hugh has two ‘power weapon’ slots; one slot always dedicated to a damage-dealing beast like that shotgun, and the other home to a weapon which will offer more battlefield control. In this demo that latter weapon was a ‘Stasis Net’ which held approaching enemies still for a short time while dealing minimal damage. Diana’s hacks, meanwhile, will grow over the game via a suite of power-ups.

Through this, there’s a hope that players can have a good amount of freedom of expression in their play. Plus, there’s no one prescription for enemies – a shooter fan might play more ballistics-heavy, while someone who gets really into the hacking might do the opposite; Pragmata has been carefully designed to work both ways.

“Depending on the player… Well, they might want to play it safe – use the Stasis Net, back off a bit, and then hack and go for careful shots,” Oyama outlines. “Or I can go in hung-ho – skip the Stasis Net, and straight up hack and shoot.

“Also, the actual hacking itself does damage. With that in mind, you can have a playstyle that’s really focused on hacking, or you can hack the enemy once and then just go for shooting outright. So there’s a sort of balance in what you can do there.”

Part of the challenge of a game like this, with unique and strange systems, is that they can be a difficult sell. It’s plain that it was a difficult thing for Capcom to figure out internally throughout development. Pragmata now works – I can’t wait to play it – but now an arguably even more difficult task is on the horizon – how to explain and sell these mechanics to the public. Even describing it all in a preview is difficult, other than to say: it’s strange, and I love it.

“There’s a bit of a difference in the experience between watching videos of Pragmata and actually getting your hands on a controller, knowing it, and getting immersed in the game. In fact, it’s really different,” Oyama says. There’s a passion in his delivery of this statement – and plainly a clear belief that this team has made something special.

“We’ve worked hard, long years to get something here that people enjoy. And we’re just really glad to see that people are enjoying the game that we put so much time and so much effort into,” Oyama concludes.

He’s hoping that off the back of some strong trade show responses, Pragmata’s unique blend of mechanics can find a broad audience. Honestly, based on what I’ve experienced so far, I hope so too. We need more mad, weird experiments like this, after all.