In the year 2025, it’s admittedly hard to care about a World Expo, though I am perhaps an outlier drawn to the spectacle of national branding under the banner of bringing humanity together (all the “civilised” parts of it, anyway).

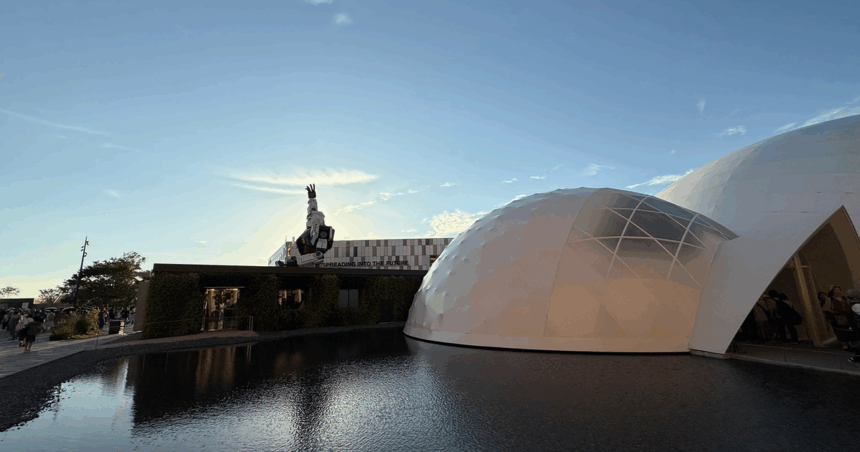

This year’s Expo was held in Osaka, which last hosted an Expo in 1970 featuring the Tower of the Sun – a singular monument I visited a few years ago that remains undefeated in weirdness and wonder. Back then the Tower of the Sun’s creator, Tarō Okamoto, filled it with a surreal vertical exhibit that depicts the evolution of life; the 2018 film Tower of the Sun suggests that Okamoto meant for his creation to challenge the Expo 70 theme “Harmony and Progress for Mankind,” because humanity hadn’t yet achieved or earned either of these things.

I think about this a lot more than I should, mostly because I have a Tower of the Sun statuette above my television, but also because the flaws of the Expo’s techno-optimistic, tomorrow-focused social attitudes have become, somehow, even further out of step with reality.

In Osaka 2025, we have Gundam and Astro Boy and Sanrio and the bafflingly endearing multi-eyed mascot Myaku-Myaku. We also have a climate change-powered heatwave, WiFi, and a lot of walking, which is arguably the hallmark of any Expo – I also murdered my feet at the 2010 Shanghai Expo, which was the largest in modern expo history. But most of all, I recognise the bewildering yet seamless mental transition between the expensive, sprawling sociopolitical circus in front of me, and the tar-coated digital one at home, where I left Sam Porter Bridges vibing in the middle of a post-Death Stranding Australia.

On the most cosmetic of surfaces, it is pretty funny to look at the obvious ha-ha commonalities between Death Stranding and the World Expo: the core rhetoric of building bridges both literal and figurative, connection for the greater good, better living through technology. Both follow a protocol that outlines how all of these structures should be dismantled or reused. There is, throughout the course of a day at the Expo and likewise down under in Hideo’s Ozjima, a great deal of route-planning, strategy, opportunism, waiting, walking, and sweating.

The first modern world expo, the Great Exhibition in London in 1852, was so successful that it structurally improved design education in England as a whole; design improvements through dialogue and better infrastructure is a key part of Death Stranding’s concept. There are all sorts of niche gadgets being deployed to combat the weather – lightweight vests and jackets with built-in, battery-powered fans are all the rage amongst tourists and outdoor workers like security guards and event staff. Sure, there’s the godawful heat and physical suffering, but there are also stamina-boosting iced teas and cute dangly backpack accessories.

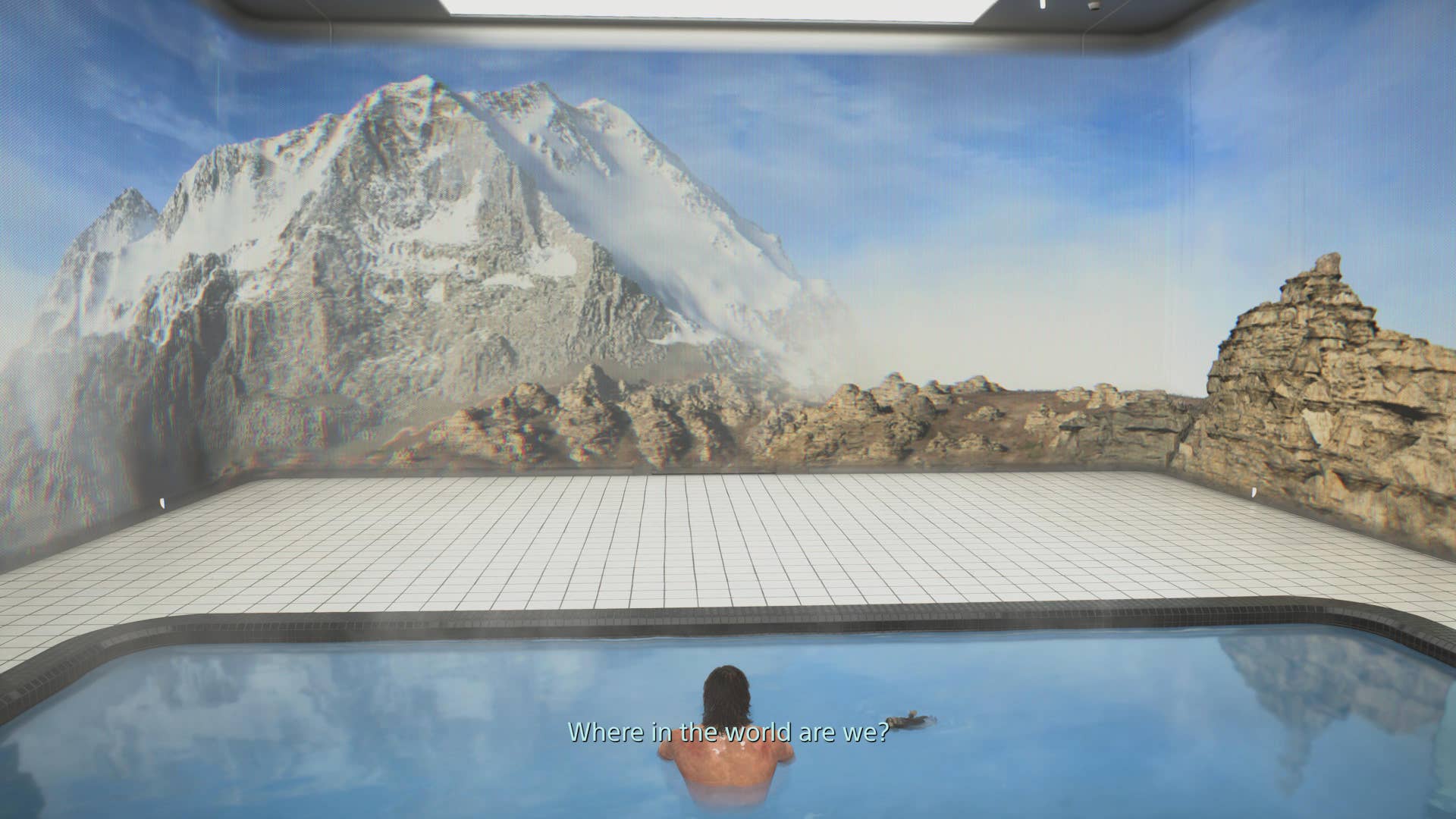

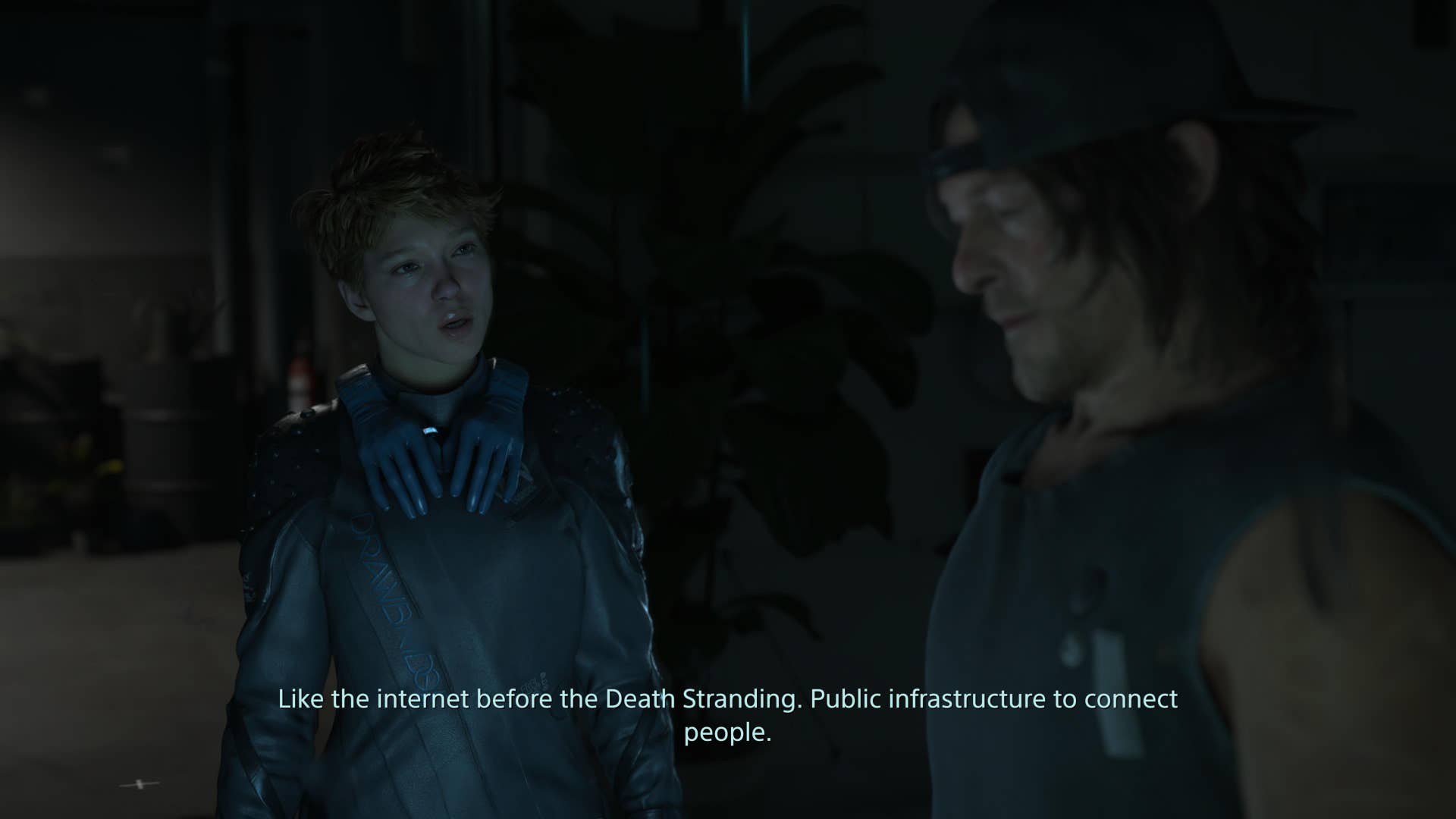

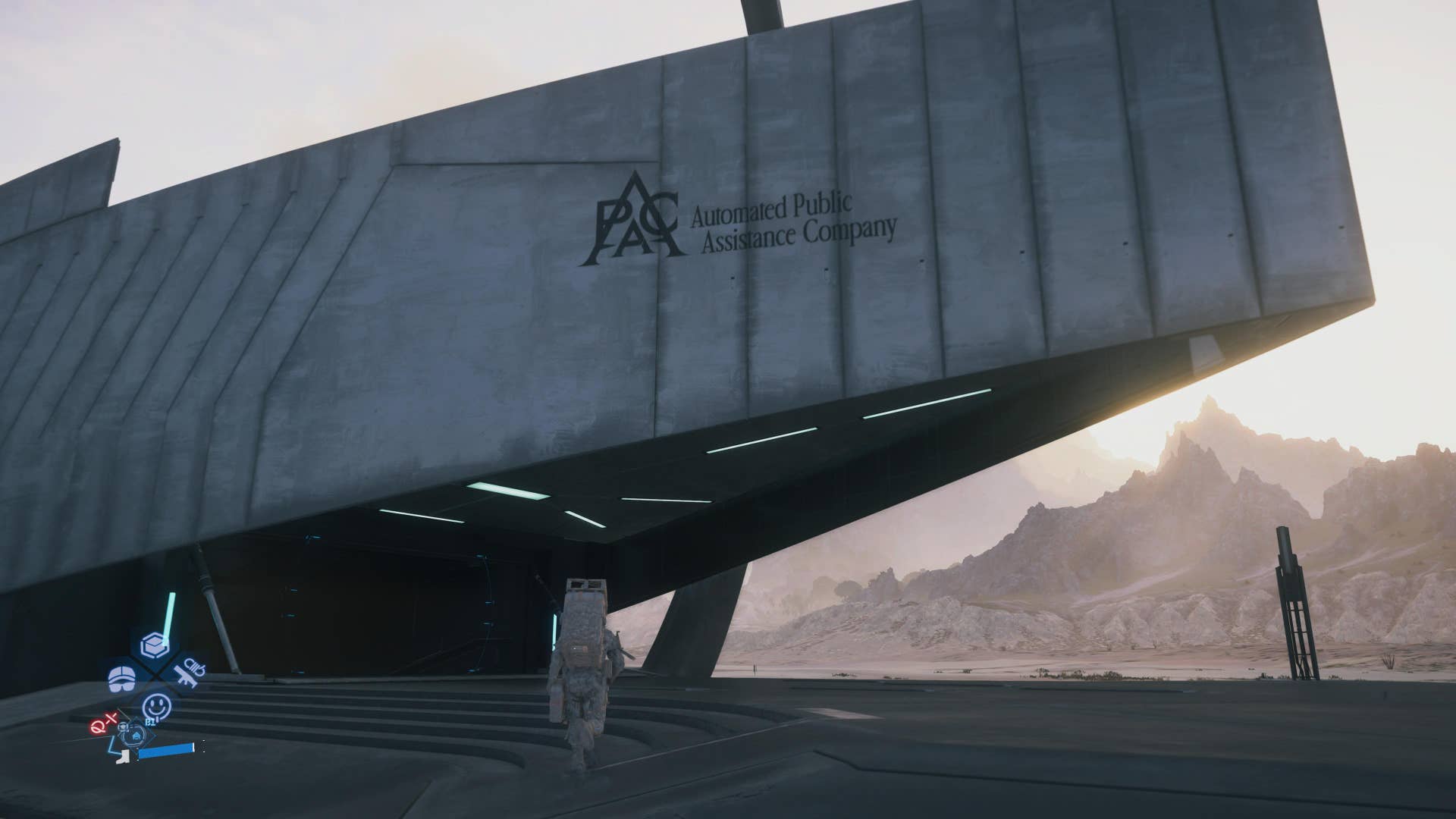

But most of all, there is a relentless panglossian focus on the rosy promise of tomorrow – a better world, with better social and technological practices – that drives both of these entities forward like a Monstered-up tour guide working on commission. In Death Stranding 2, Sam is asked to connect Mexico to the chiral network, and then Australia, which was cut off during the titular stranding event; Bridges is no longer around, and has been replaced by a private corporation, APAC, and Fragile’s new outfit, Drawbridge, which serves to connect everywhere outside of North America. Every step that Sam takes, as we are constantly reminded, is a step closer to a more unified whole.

Because it’s a Kojima game, we even literally have a character named Tomorrow – Elle Fanning – to really spell the theme out for you in childlike platinum-blonde letters. “Tomorrow” is also a big Expo theme – an obvious component of futurism as a whole. Many of the robotics on display at the Expo are all tomorrow-fied prototypes and proof-of-concept machines designed to ostensibly improve life in the future. For instance, the Yamaha Motoroid 2, an experimental bike designed as an indispensable “lifetime companion” made to evoke the feeling of kando, “the simultaneous feelings of deep satisfaction and intense excitement that we experience when we encounter something of exceptional value,” as a bit of nearby signage put it. In Yamaha’s words, the bike is a responsive “unknown life form” designed to work with human thoughts, physical stimuli, and haptics that will supposedly revolutionise the rider’s posture by freeing the upper body, sort of like a cyborg centaur.

Each nation’s pavilion is a neatly demarcated depot for visitors to learn about said country’s industries and economies (the queues to get in many of the pavilions are tedious, the lottery system for special pavilions even more so). In the past, the designs and structures that arose from a World Expo would have a defining impact on the host country’s architecture – the Eiffel Tower, for starters, and the 1893 Chicago Expo. And so it is with Death Stranding 2’s APAC (and Drawbridge, which uses the same chiral technology and infrastructure), which has apparently been so expansive and so industrious that it has all these ready-to-go depots all the way down under.

It is therefore extra funny (and unsurprising) that Death Stranding 2 will remind you, at every opportunity, that its institutions aren’t inherently bad, nor do they want to expand – they just want to connect people. To build bridges. To create the network; (warning: slight spoiler in the rest of this sentence!) one that will ultimately open a literal door to another continent, so on, and so forth. But I suppose if the Expo was once seen as “the world’s university,” Sam’s meandering journey through time and space is also one of discovery and edification.

In Osaka, I learn about Teranga, an important Senegalese value that invokes hospitality, solidarity, and community, as well as the country’s goals for “full digital transformation.” In the special Blue Ocean Dome, I learn about an edible yeast-based detergent that can “wash and freeze human cells.” I gaze at an Algerian industry poster that depicts the 422km Western Mining Line and the 1650km Eastern Mining Line to “connect communities, drive economic growth, and mark a new age of progress”. It’s an endless swathe of pristine orange desert, cut neatly in half by a perfectly straight railway line. If these guys had Drawbridge technology, I think, maybe we could really cook.

The thing is, it’s tiring to be fed a constant diet of tomorrow-ism, when the present is killing the most vulnerable of us. It is cognitive whiplash to see all the promised treasures in our bright, shiny roboticised future followed by a stroll through the unmanned Palestine booth, filled with beautiful examples of crafts and culture that are completely unmoored from the ongoing Palestinian genocide. It is horribly, bleakly funny in such a rabidly anti-migrant world to see a diversity placard in the European Union pavilion directing visitors to “learn about Europe’s new travel requirements.” The US pavilion is a looming, featureless metal processing center, that perfectly resembles the kind of dystopian immigration and customs checkpoint that might be designed by Christopher Nolan. When critics talk about the Expo outliving its function as a place of education in the internet era (or even edutainment, since it has historically become mostly about entertainment), it is exceptionally easy to see why.

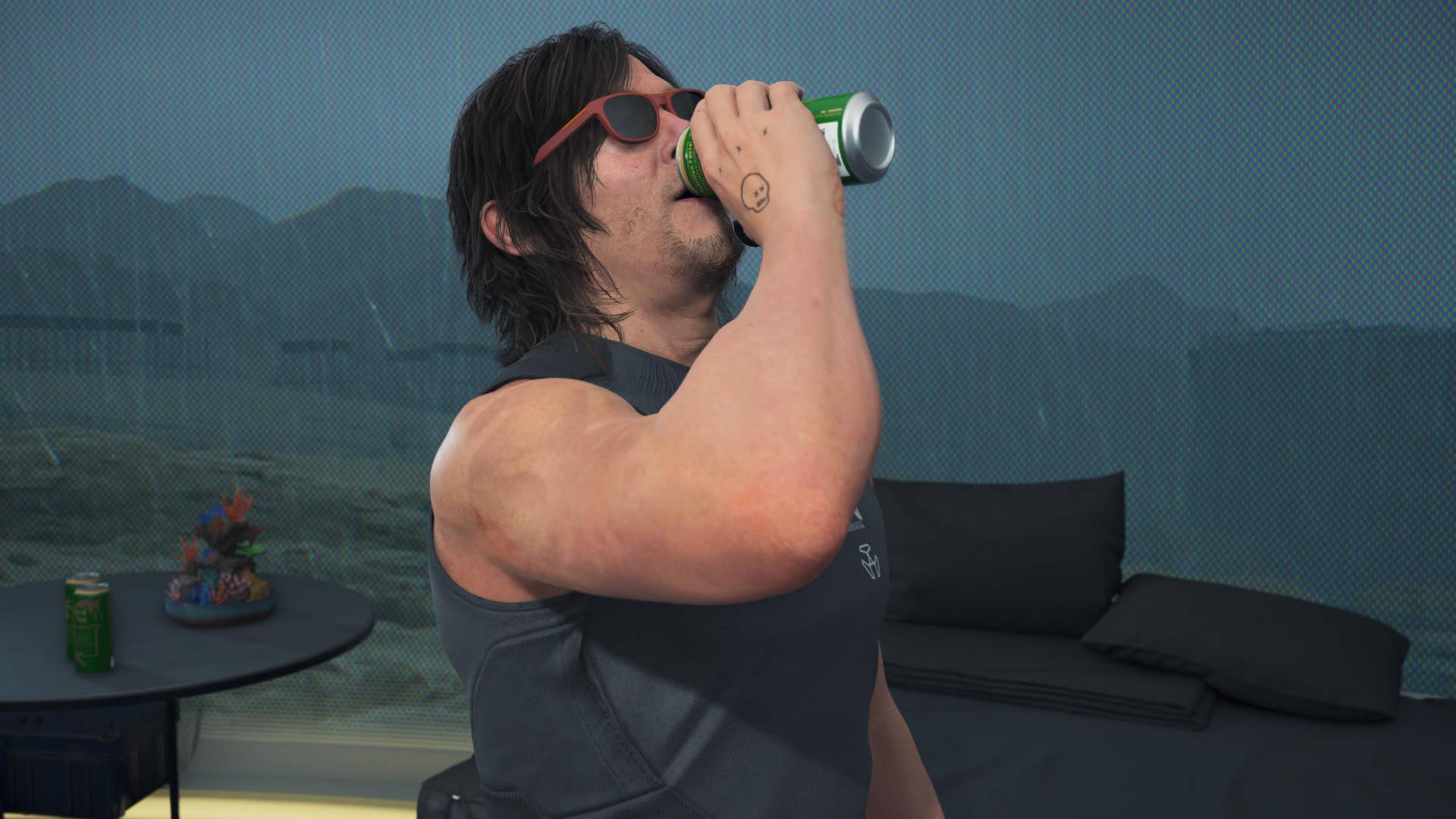

Eleven kilometers of walking in 40C heat later, I start to think hard about the absurd fantasy-tomorrow lying dormant in my PlayStation. Death Stranding, with all its sloggy arena fights and godawful writing, is, on an emotional level, absolutely untouchable when it comes to building a better, connected world. It is impossible, in 2025 – a time when we know more than we need to about how things work, and yet also somehow not nearly enough – to embrace techno-optimism without sounding dangerously naive. But the fact is, I can’t stomach real-world talk about benign, gentle technofutures and well-meaning corporations anymore (and I was a kid who grew up on my dad’s paper subscription to Wired). If you’re going to sell me a collective dream – one that everyone is genuinely rooting for, then sell it to me in the form of tired Norman Reedus in special Gentle Monster collaboration sunglasses, because that actually works.

The Expo, for all its delightful window dressing (look, I bought a ton of souvenirs, I’m guilty), is the world’s biggest business fair for developed nations. Its agenda isn’t actually to build a better tomorrow, it’s to talk about a better tomorrow – so really, business as usual, but with nicer optics. It is no longer the same project that began as a global showcase for industrialisation, nor is it a vehicle for grand cultural exchange (it did, of course, also feature degrading exhibits of indigenous peoples, as befitting the interests of colonial minds). As of 1988, we’re in the Expo’s nation-branding era.

And if we’re being real, nobody here is looking for connection. My original idea for this story was to talk to people about their thoughts on connection and community, but everyone I approached – with the exception of one official delegate at the India pavilion who was all about business – didn’t want to chat. I’m not sure if it was the unbearable heat and discomfort, the fact that we were all visibly exhausted, or the words “just a short interview, a couple of questions,” but I can’t blame them – it was all overwhelmingly tiring.

Historian Robert Rydell wrote, on the subject of the 1962 World’s Fair, that “America… needed the world’s fair to reinstill faith in itself.” If we’re still trying to do that today, I think it’s safe to say it’s not working. If you read about public sentiment during the lulls between world expos, there are robust feelings on display: postmodern skepticism, disgust at fat pavilion budgets during lean times, childlike wonder, disillusionment, and so on. But what always seems to prevail is a quaint, evergreen optimism for the supposed universal values and ideas that a world expo is supposed to represent.

When Tarō Okamoto got weird with the Tower of the Sun back in 1970, he was right – humanity wasn’t and still isn’t doing great in the harmony and progress department. Maybe the answer wasn’t to assuage each nation’s self-confidence in the form of exorbitant (but mostly temporary) aesthetic public works, but to recognise that it’s really tough to sell a slick sci-fi future to people who are barely making it in the present.

Death Stranding 2 is as far removed from reality as it possibly can be on so many levels, except arguably the most important one – Kojima and co. are masters of weaponising optimism to elicit the correct (and sometimes the most maudlin) emotions about one’s place and purpose in a much bigger world. Tomorrow rightfully doesn’t know what the hell she’s doing for a lot of the game, or how she’s going to fit into the bigger picture of the world (there are also some really corny pop quiz segments where you have to teach her basic logic) – and you know what? That’s real. That’s relatable. Girl, neither do I.

If we’re going to dream big, don’t feed me more marketing slop about half-sentient motorbikes or turbo-niche saltwater tonics that affect environmental sustainability. Give me the little talking marionette doll and cool sky races against ghost mechs. (While we’re at it, Kojima, please give us back our piss bombs and piss cutscenes). Give me a silly side quest where I deliver a literal piece of Uluru – Australia’s most sacred indigenous site that has been routinely abused by colonisers as a nice big tourist rock – to a K-pop boyband doppelganger called The Pioneer.

Death Stranding 2’s tagline is “Should we have connected?” – and seeing what’s out there in the real world’s alternative, at the one place that has historically advertised itself, for centuries, as a place of connection and shared innovation, I say: hell yes! Give me that sweet chiral juice.